Chinese Calendar

The lunar calendar (nóng lì) is a traditional Chinese calendar. The beginnings of the Chinese calendar can be traced back to the 14th century B.C.E. Legend has it that the Emperor Huangdi invented the calendar in 2637 B.C.E. The Chinese calendar is based on exact astronomical observations of the longitude of the sun and the phases of the moon. This means that principles of modern science have had an impact on the Chinese calendar.

The lunar calendar (nóng lì) is a traditional Chinese calendar. The beginnings of the Chinese calendar can be traced back to the 14th century B.C.E. Legend has it that the Emperor Huangdi invented the calendar in 2637 B.C.E. The Chinese calendar is based on exact astronomical observations of the longitude of the sun and the phases of the moon. This means that principles of modern science have had an impact on the Chinese calendar.Chinese New Year is the main holiday of the year for more than one quarter of the world's population. Although the People's Republic of China uses the Gregorian calendar for civil purposes, a special Chinese calendar is used for determining festivals. Various Chinese communities around the world also use this calendar.

Chinese Calendar-Making

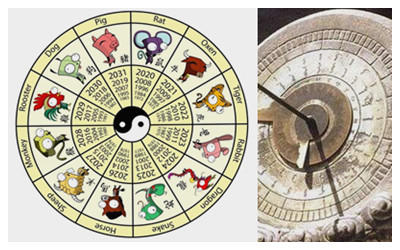

An important aspect of the Chinese calendar is the sexagenary cycle (gan zhi), which is 60 years long. This is a combination of the 10 heavenly stems (tian gan), and the 12 earthly branches (di zhi). The following is a table showing the sexagenary:

| Stems | 天干 | tiān gān | Element | Branches | 地支 | dì zhī | Animal |

| 1 | 甲 | Jiǎ | Wood | 1 | 子 | zǐ | Rat |

| 2 | 乙 | Yǐ | Wood | 2 | 丑 | chǒu | Ox |

| 3 | 丙 | bǐng | Fire | 3 | 寅 | yín | Tiger |

| 4 | 丁 | dīng | Fire | 4 | 卯 | mǎo | Rabbit |

| 5 | 戊 | Wù | Earth | 5 | 辰 | chén | Dragon |

| 6 | 己 | Jǐ | Earth | 6 | 巳 | sì | Snake |

| 7 | 庚 | gēng | Metal | 7 | 午 | wǔ | Horse |

| 8 | 辛 | Xīn | Metal | 8 | 未 | wèi | Goat |

| 9 | 壬 | Rén | Water | 9 | 申 | shēn | Monkey |

| 10 | 癸 | Guǐ | Water | 10 | 酉 | yǒu | Chicken |

| 11 | 戌 | xū | Dog | ||||

| 12 | 亥 | hài | Pig |

Great importance was attached to the celestial observation in making a new calendar during ancient China. The gnomon (a column for measuring the sun's meridian altitude) and sundial were the timekeeping instruments with the sun as the object for observation. Although simple structures, the two instruments could serve many purposes, and were said to be China' oldest astronomic instruments.

By the middle of the Spring and Autumn Period (770-446 BC), to use the gnomon for making a calendar had become an important calendar-making method, through which the conclusion of a tropical year being 365.25 days long was reached.

Chinese lunar calendar

The Chinese lunar calendar is a traditional calendar in China and it is also called Xia Li or Yin Li. It is based on exact astronomical observations of positions of the sun and moon. Thus in essence it is a combined solar/lunar calendar.

In the calendar, one year is divided into 12 months and the months have either 29 or 30 days, always beginning on days of astronomical new moons. So each year has 354 or 355 days. To make the average length of the years equal to a tropical year, an intercalary month is added every two or three years.

As a result, an ordinary year has 12 months while a leap year has 13 months. And an ordinary year has 354, or 355 days, and a leap year has 384 or 385 days.

Jiéqì -Solar Terms

Chinese months follow the phases of the moon. The solar-based agricultural calendar is made up of twenty-four points called jieqi. They are essentially seasonal markers to help farmers decide when to plant or harvest crops, as the lunisolar calendar is for obvious reasons unreliable in this respect.

Chinese months follow the phases of the moon. The solar-based agricultural calendar is made up of twenty-four points called jieqi. They are essentially seasonal markers to help farmers decide when to plant or harvest crops, as the lunisolar calendar is for obvious reasons unreliable in this respect.

| M | Ecliptic Long. |

Chinese Name | Gregorian Date (approx.) |

Usual Translation |

Remarks |

| 315° | lichun | 4 February | start of spring | spring starts here according to the Chinese definition of a season | |

| 1 | 330° | yushui | 19 February | rain water | starting at this point, the temperature makes rain more likely than snow |

| 345° | qizhe | 5 March | awakening of insects | when [hibernating] insects awake | |

| 2 | 0° | chunfen | 21 March | vernal equinox | lit. the central divide of spring (referring to the Chinese seasonal definition) |

| 15° | qingming | 5 April | clear and bright | a Chinese festival where traditionally, ancestral graves are tended | |

| 3 | 30° | guyu | 20 April | grain rains | rain helps grain grow |

| 45° | lixia | 6 May | start of summer | refers to the Chinese seasonal definition | |

| 4 | 60° | xiaoman | 21 May | grain full | grains are plump |

| 75° | mangzhong | 6 June | grain in ear | lit. awns (beard of grain) grow | |

| 5 | 90° | xiazhi | 21 June | summer solstice | lit. summer extreme (of sun's height) |

| 105° | xiaoshu | 7 July | minor heat | when heat starts to get unbearable | |

| 6 | 120° | dashu | 23 July | major heat | the hottest time of the year |

| 135° | liqiu | 7 August | start of autumn | uses the Chinese seasonal definition | |

| 7 | 150° | chushu | 23 August | limit of heat | lit. dwell in heat |

| 165° | bailu | 8 September | white dew | condensed moisture makes dew white; a sign of autumn | |

| 8 | 180° | qiufen | 23 September | autumnal equinox | lit. central divide of autumn (refers to the Chinese seasonal definition) |

| 195° | hanlu | 8 October | cold dew | dew starts turning into frost | |

| 9 | 210° | shuangjiang | 23 October | descent of frost | appearance of frost and descent of temperature |

| 225° | lidong | 7 November | start of winter | refers to the Chinese seasonal definition | |

| 10 | 240° | xiaoxue | 22 November | minor snow | snow starts falling |

| 255° | daxue | 7 December | major snow | season of snowstorms in full swing | |

| 11 | 270° | dongzhi | 22 December | winter solstice | lit. winter extreme (of sun's height) |

| 285° | xiaohan | 6 January | minor cold | cold starts to become unbearable | |

| 12 | 300° | dahan | 20 January | major cold | coldest time of year |

Note: The third jieqi was originally called (qizhe) but renamed to (jingzhe) in the era of the Emperor Jing of Han (hanjingdi) to avoid writing his given name qi.

Ask Questions ?

Ask Questions ?