Skype: neodalle-travel

Tel: +86 135 7447 2266

E-mail: sales@visitaroundchina.com

The Pattra-Leaf Culture is a symbolic term referring indirectly to Dai Culture. Pattra is a kind of woody palmate plant growing in tropical and subtropical areas. The Dai use pattra leaves as a medium of written language and thus endow this natural substance with a particular touch of culture.

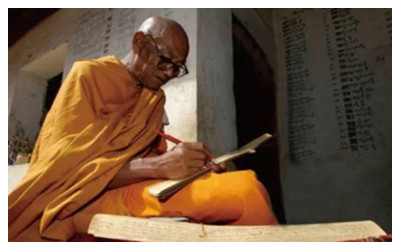

The Pattra-Leaf Culture is a symbolic term referring indirectly to Dai Culture. Pattra is a kind of woody palmate plant growing in tropical and subtropical areas. The Dai use pattra leaves as a medium of written language and thus endow this natural substance with a particular touch of culture.Since almost all Dai people were Buddhist, the essence of the Pattra-Leaf Culture was mainly preserved in Buddhist scriptures written in the Dai language. It is said that sutras preserved in the Buddhist circle of Xishuangbanna amount to more than 84, 000 fascicules, all bulky and voluminous; these sutras fall into four major categories, namely Sinayapitaka (21,000 volumes), Vinayapitaka (21,000 volumes), and Adhighatmapitaka (42,000 volumes) and the annotative and interpretive classics of these sutras. These sutras in various versions, either in Bali transliteration or in Dai translation, or in Bali transliteration with Dai annotations, serve a vital function in retaining the 0riginal features of Southern Buddhist classics. For instance, in Sinayapitaka are the most familiar Jataka Sutras with 547 stories about the life of Sakyamuni; Vishendoro, the last of the stories, for example, was so much adored by the Dai in Xishuangbanna that it still exerts influence on their Buddhist services, daily activities and customs. In fact it has been held as a religious norm observed even by laymen.

In addition to Buddhist scriptures, there are annotative works by generations of eminent Dai monks and scholars. These works involve astronomy, almanacs, history, medicine, language, literature, sports and customs, covering so many fields that they could be regarded as a Dai encyclopedia; though not included in the authentic Buddhist sutras, they have been kept in the Buddhist monasteries and passed down in the form of classics.

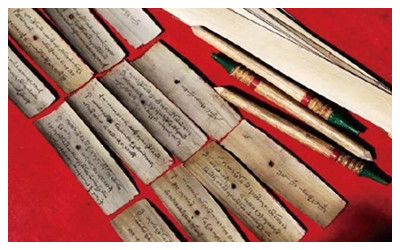

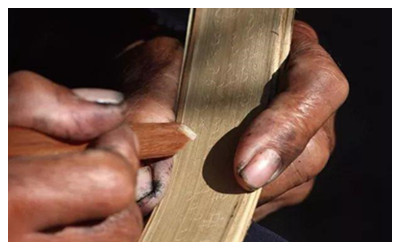

Buddhist sutras and other works engraved on pattra leaves are called pattra-leaf scriptures. The making of pattra-leaf scriptures is an exquisite process divided generally into two steps, namely preparing leaves and engraving scriptures. To prepare pattra leaves, first raw leaves are collected and bound into bundles with three to five leaves in each; the bundles were put into a cauldron to boil with a proper amount of tamarind or lemon added. When these bundles are properly cooked, they are rubbed with fine sand, cleaned in water and dried in the sun; then flattened and trimmed to a size about 50 to 60 cm long and 8 cm wide, and kept 500 to 600 pieces in a box for use. Before engraving, the pattra leaves have to be grated with a thread ink-marker on both faces with 5,6,or 8 lines on each; put the grated leaves on a wooden rack and engrave scriptures with a cutting stencil. When the engraving is finished, powdered carbon and oil are applied on the nicking and to clear up the face. The work of engraving is generally brought to a temporary close when 10 to 20 leaves are done, and then a fascicule is bound with gold powder or red (black) lacquer applied along the sides. With decorations,

Buddhist sutras and other works engraved on pattra leaves are called pattra-leaf scriptures. The making of pattra-leaf scriptures is an exquisite process divided generally into two steps, namely preparing leaves and engraving scriptures. To prepare pattra leaves, first raw leaves are collected and bound into bundles with three to five leaves in each; the bundles were put into a cauldron to boil with a proper amount of tamarind or lemon added. When these bundles are properly cooked, they are rubbed with fine sand, cleaned in water and dried in the sun; then flattened and trimmed to a size about 50 to 60 cm long and 8 cm wide, and kept 500 to 600 pieces in a box for use. Before engraving, the pattra leaves have to be grated with a thread ink-marker on both faces with 5,6,or 8 lines on each; put the grated leaves on a wooden rack and engrave scriptures with a cutting stencil. When the engraving is finished, powdered carbon and oil are applied on the nicking and to clear up the face. The work of engraving is generally brought to a temporary close when 10 to 20 leaves are done, and then a fascicule is bound with gold powder or red (black) lacquer applied along the sides. With decorations,  wrapping satchels or holding boxes added, fascicules would be lovely and damage-resisting. A full-length pattra-leaf sutra may fill 10-20 fascicules, and the advantage of pattra-leaf classics is the possibility of being kept for several or even dozens of centuries since they are immune from insects, borers, weathering or decomposing.

wrapping satchels or holding boxes added, fascicules would be lovely and damage-resisting. A full-length pattra-leaf sutra may fill 10-20 fascicules, and the advantage of pattra-leaf classics is the possibility of being kept for several or even dozens of centuries since they are immune from insects, borers, weathering or decomposing.

The choice of pattra leaves for a medium in writing reflects Dai's intelligence and resourcefulness. At the outset, the engraving of pattra leaves was limited to keeping Buddhist scriptures, but as society and culture develop, this means was extended to an increasing variety of political events, business transactions, legal affairs, artistic activities and so on. The Pattra-Leaf Culture cannot cover Dai culture in a broader sense of course, but is certainly the most striking part that has made an indelible contribution to the accumulation, dissemination and prosperity of this culture. As a treasure house for researches into the traditional Dai culture, the Pattra-Leaf Culture is not only a gem of the Dai culture but also an enchanting branch in the Chinese culture and world cultures.

Ask Questions ?

Ask Questions ?