Imperial Examination System

History of the Examination

The origins Chinese examination system (Kējǔ or 科举 in Chinese) was held in the early Han dynasty when wise rulers figured out that the way to avoid officials building power bases from their family and friends was to appoint on basis of talent. In 165BCE Emperor Wendi introduced a system of examinations testing the knowledge of the Five Confucian classics. The Grand Academy 太学 tài xué was founded in 124 BC. The Four Books and Five Classics (Book of Documents, Book of Songs, Book of Changes, Book of Rites and Book of Ceremonies) were the core texts. Candidates would also be set a question on current affairs. Later stress on agriculture and ethics were incorporated into the system and the Ming Jing (Expertise in Classics) grade was introduced.

As an important way to select officials, the imperial examination system was started in the Sui Dynasty (581-618). Emperor Yangdi initiated imperial examination system in 606AD, which was also called Keju System.

This system was further developed in the Tang Dynasty (618-907AD). In the Song Dynasty (960-1279AD) the emperors attached more importance on the examination. The system only really became a significant institution under the Tang, previously it had been used sporadically and only for few appointments. Its administration became one of the four principal directorates. By the end of the Song dynasty times as many as 400,000 candidates took the exams, but only about 1 in 300 passed; and only those who succeeded could expect a lucrative post in central government. Each province had to put forward at least three candidates for office each year. Written examinations were used to select Xiu Cai 秀才 (Flowering talent) scholars roughly equivalent to a bachelor's degree. Tang Emperor Taizong introduced the Ju Ren 举人 (Raised man) grade, roughly equivalent to a master's degree. The third level was the Jin Shi 进士 (Advanced Scholar) which is roughly equivalent to a doctorate. Those that passed the first, local Shenyuan ( 生员) exams automatically received minor privileges such as exemption from forced labor, effectively becoming middle class. Half of the candidates had no family history of passing the examination. The Emperor often took personal control of the examination system, reading the essays submitted for the highest levels. The top students at the top level were admitted to the prestigious Hanlin Academy. The academy was a pool of talent used for many Imperial purposes such as educating the Emperor's sons, drafting edicts and administering the whole examination system. To become a Hanlin academician was the pinnacle of academic achievement and brought with it great respect.

The

system became more sophisticated during the reign of the first Ming dynasty Emperor Hongwu in 1382. Each prefecture (local district) had to have a school. Scholars who reached the Xiu Cai grade could then enter a provincial examination for the Ju Ren 举人 grade, held normally every three years. To pass this examination took years of study and it was rare for a candidate to be ready to take it before they reached the age of 30. The few that passed (5 to 10%) could then compete at national level at the capital city Beijing for the Jin Shi 进士 (Advanced Scholar) grade. To succeed at this level it was normal to have a patron who had been impressed by their scholarship and would then help with the candidate's studies and finances. Often a promising young boy would be supported by a syndicate of extended family and friends who would pay for materials, tutors and books. The successful official would then pay back his supporters and patrons with money, appointments and other benefits. A student would normally study in one of the many Academies (书院 shū yuàn) to prepare for the examination. If the Jin Shi examinations were passed the lucky candidate would be offered a permanent and lucrative post in government. During the Ming dynasty only about 200 candidates passed at this level each year; so there were only about 3,000 top scholars at any one time in the whole of China.

system became more sophisticated during the reign of the first Ming dynasty Emperor Hongwu in 1382. Each prefecture (local district) had to have a school. Scholars who reached the Xiu Cai grade could then enter a provincial examination for the Ju Ren 举人 grade, held normally every three years. To pass this examination took years of study and it was rare for a candidate to be ready to take it before they reached the age of 30. The few that passed (5 to 10%) could then compete at national level at the capital city Beijing for the Jin Shi 进士 (Advanced Scholar) grade. To succeed at this level it was normal to have a patron who had been impressed by their scholarship and would then help with the candidate's studies and finances. Often a promising young boy would be supported by a syndicate of extended family and friends who would pay for materials, tutors and books. The successful official would then pay back his supporters and patrons with money, appointments and other benefits. A student would normally study in one of the many Academies (书院 shū yuàn) to prepare for the examination. If the Jin Shi examinations were passed the lucky candidate would be offered a permanent and lucrative post in government. During the Ming dynasty only about 200 candidates passed at this level each year; so there were only about 3,000 top scholars at any one time in the whole of China.In Qing Dynasties, the branch tested was only one and the contents tested were limited to “the Four Books”, namely the great Learning, the Doctrine of the Mean, the Analects of Confucius and Mencius and “the Five Classics”, namely, the Book of Songs, the Book of History, the Book of Changes, the Book of Rites and the Spring and Autumn Annuals. All the candidates had to write a composition explaining ideas from those books in a rigid form and structure, which was called Eight Part Essay. To start with, two sentences should be used to tell the main idea of the title, which was called “to clear the topic”. Then it should be followed by several sentences to clarify the meaning of the topic, which was called “to continue the topic”. The remaining part had to carry on discussions on the topic in the form of parallelism and antithesis, which was rigidly restricted. The ideas must tally with the ideas from the Four Books and the Five Classics. Liberal ideas were not accepted. The examination was held once every three years. It had four levels: the county examination, the provincial examination, the academy examination and the palace examination. Only when one passed the lower level examination was qualified to attend the next examination. All the candidates for the county examination were called tongsheng. Those who passed were called Xiucai. Those who passed the provincial, the academy and the palace examinations were called Juren, Gongshi and Jinshi respectively. The first three of Jinshi were ranked Zhuangyuan, bangyan and tanhua respectively. All the jinshi would be given a post by the emperor. Their names would be engraved on the tablets.

The imperial examination system was terminated in 1905.

Features of the examination

As there was no age limit, candidates could retake the examinations many times if they failed. So the temptation for those who just failed to reach the grade was to try again and again. A well attested case is of a candidate continuing to take the examinations until he passed at the age of 72. The chief difference to modern education is that examinations did not follow a rigorous age-related. Some candidates repeatedly presented themselves for examination throughout their lives. This was not considered odd or exceptional.

Senior officials showed interest in the examination questions that had been set each year and acted as patrons and mentors for bright candidates who they were acquainted with. In this way study, among the scholarly, was a life-long passion and constant source of news and debate.

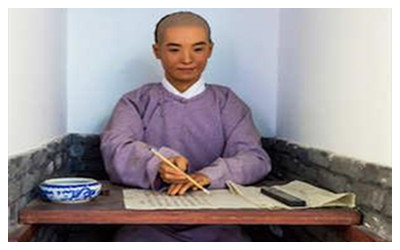

A typical examination involved being locked inside the examination hall for several days and nights so candidates could not cheat, the essay they produced was marked on strict criteria.

The imperial examination really played an important role in the feudal times in China. It had great influence on Chinese people. By this way the talents were found and selected by the emperors to serve the feudal government. At the same time the contents of the examination was so dull which confined the thoughts of the intellectuals.

Ask Questions ?

Ask Questions ?